“Bad Lieutenant” gets one thing right: It’s bad.

On its surface, Werner Herzog’s Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans explores appropriately Herzogian themes. Having often considered the futility of personal ambition (Fitzarraldo, Aguirre, Grizzly Man) and the illusory nature of the American Dream (Stroszek), abuses of power and fraudulent “justice” systems would seem likely enough subjects for the auteur. But the film, deeply grounded in an audacious performance by Nicolas Cage in the title role, left me finally scratching my head.

Herzog’s film may or may not be inspired by the 1992 Abel Ferrara Bad Lieutenant, depending whom you ask. For starters, there’s a new character name, and this version is set in New Orleans, beginning immediately after Hurricane Katrina–a decision which brims with potential significance. Herzog told Defamer the new setting was partly “a decision of the producers for tax incentives,” but also presented “a particularly interesting set-up. The neglect and politics after the hurricane struck are something quite amazing. It has to do with public morality.” (1) He’s absolutely right, of course. The “corrupt cop” may be a familiar meme, but it’s merely a microcosm here: the indulgent, corrupt, and utterly reckless actions of the individual must be considered within the context of failure and abandonment that permeated every level of authority to create the mess that Katrina became. Cage’s McDonaugh uses his position almost entirely for his own impulses, investigating crimes along the way only as it suits him. He makes threats, plants evidence, and steals confiscated property with barely concealed glee, and instead of being fired, he gets promoted.

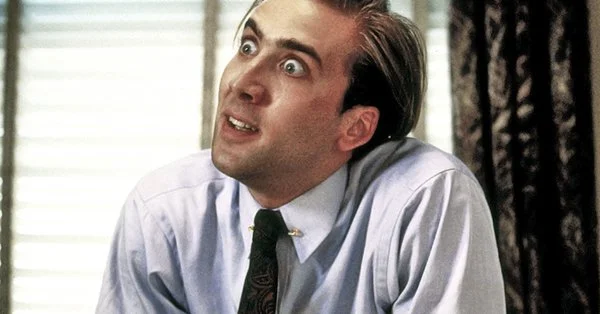

Cage in Werner Herzog’s Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans

Cage brings a barely restrained mania to his role, and the effect is mirrored in other quirky Herzog additions to the script (e.g., extreme close-ups of iguanas and a breakdancing soul). All of this adds to the film’s watchability–sometimes it’s even wildly entertaining–but the resulting hysteria reads more as slapstick than social commentary. Sure, the actions portrayed are shocking, but they are also completely surreal; with no hint at real-world motivations or plausibility, the picture that emerges is ultimately not a threat. Still, the subject is too true to merely dismiss with pure comedy, so the result is a sense of arch irony–almost a defiant refusal to care–and the audience at my showing giggled loudly throughout to show they were in on the joke. I might expect this sensibility coming from Tarantino, but it’s one I have trouble reconciling with what I know of Herzog.

The movie lacks a traditional plot, but as Cage’s lieutenant fumbles through his surroundings, they slowly begin to transform. He closes his case (if unjustly) and those around him get their lives on track; it’s almost as if his influence is positive despite himself. If McDonaugh is a metaphor for (or microcosm of) the US, then perhaps this is ultimately the message–that despite its suspect motives and its brazen disregard, our country sometimes manages to do good anyway. Nonetheless, I can’t help feeling Herzog set out to illustrate the farce of American justice, and wound up simply made a farcical film.

(1) “Defiant Werner Herzog to Defamer: ‘Who is Abel Ferrara?'” http://defamer.gawker.com/395038/defiant-werner-herzog-to-defamer-who-is-abel-ferrara

Tagged as: movies, pop culture